By Muchengeti Hwacha, Johannesburg intern.

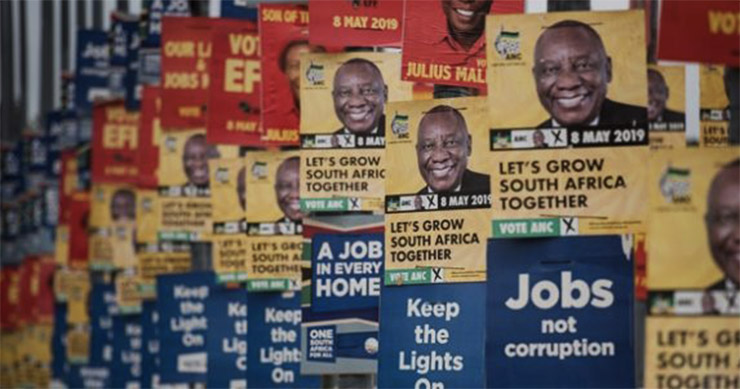

On 8 May 2019 South Africans went to the polls for national and provincial (general) elections for only the sixth time in the democratic Republic’s short 25 year history, and only the fifth time that the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC) facilitated the election process. Despite that relatively short history the IEC has managed the monumental task of holding regular elections that have been deemed both free and fair by local, regional and international observers. At this critical time in South Africa’s democratic history I am proud to say that I assisted in a successful election process. Upon the recommendation of the national director, I was appointed to form a part of the IEC’s Gauteng conflict mediation panel. I was honoured to participate in deepening the roots of this fledgling democracy.

The IEC received a significant amount of criticism following the elections. However, at the risk of being deemed conflicted, I would like to provide some context for the enormous task that the IEC takes on every five years.

The IEC was formed on 17 October 1996 as one of the so called ‘Chapter Nine’ institutions, established under the Constitution. These institutions are tasked with strengthening constitutional democracy in the Republic. Under section 190 of the Constitution the IEC is specifically tasked with;

(a) managing the elections of national, provincial and municipal legislative bodies

(b) ensuring that those elections are free and fair, and

(c) declaring the results of those elections within a period that must be prescribed by national legislation and that is as short as reasonably possible.

These three tasks look simple enough, but have often been the cause of violent conflict the world over, and more recently with our SADC neighbours; Kenya, Zimbabwe and the DRC. The cautionary tale of property damage and loss of life that played out in these countries illustrates the weight that is on the IEC’s shoulders every election cycle. These fears were compounded by various incidents in the lead up to the 2019 general election, including;

- The flare up of xenophobic violence in Durban

- The service delivery protests in Alexandra

- The Western Cape High Court ruling that threatened to postpone the elections

- A Constitutional Court ruling that required the voters role to include addresses

- The threatened strike action by IEC employees

The IEC is constitutionally mandated to handle all the issues above and more. Above and beyond this, the IEC was required to train, equip and mobilise a labour force of over 200 000 employees and approximately 50 000 volunteers. This staff contingent was to be spread out across 28 700 polling stations across the country. The challenge is made more onerous when one takes into account that this has to be done in co-ordination with the South African Police Service, the South African Defence Force, the National Disaster Management Centre, the various media houses, political parties and over seventeen and a half million voters. There is no private or public institution that has to mobilise that number of people, over such a short space of time.

It is within this context that the IEC had to operate, and if the statements of the various domestic and international observer missions are anything to go by, the institution succeeded. The issues that were highlighted by a number of the smaller parties and noted by the larger ones were important but overwhelmingly immaterial and negligible.

As a conflict mediator I personally witnessed IEC officials, spurred on by a commitment to the South African democratic project, going above and beyond the call of duty to serve this Republic. In what some political leaders declared the most important elections since 1994, I was honored to serve alongside them.